Tag: Folk

-

Harmonies and healing Frequencies: Musician Cinamon Blair carries On the musical legacy of her grandfather, left-handed Banjo & Guitar jazz musician Lee Blair

As I was recovering from the flu last week I decided to watch the documentary American Symphony on Netflix and it was absolutely heart-wrenching and timely and spoke to the incredible creativity required to survive a history as brutal and violent as American history. The story really reminded me of the healing and survival power…

-

The Cosmic Heart of Fiddler Anne Harris

I first discovered singer/songwriter, roots fiddler Anne Harris, through her work with trance Blues innovator Otis Taylor, who I had seen play at the Doheny Blues festival more than a decade ago. Anne recorded and toured worldwide for nearly a decade with Otis Taylor. Long time readers of this blog know how central the Blues…

-

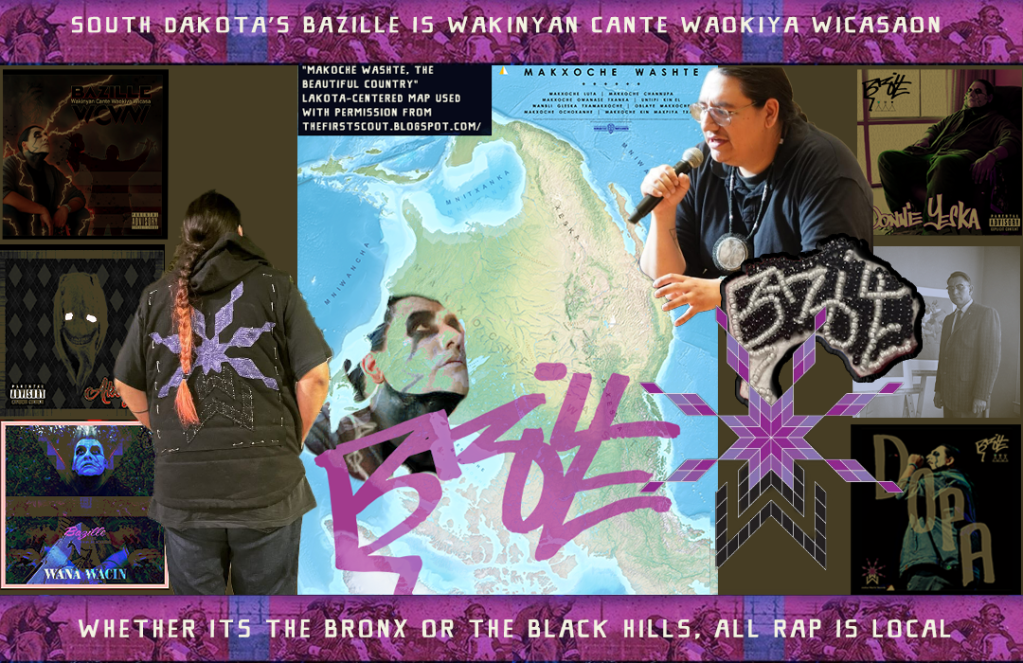

South Dakota’s Bazille is Wakinyan Cante Waokiya Wicasaon

Whether its the Bronx or the Black Hills, All Rap is Local I’ve always thought of rap as a form of folk music or street journalism such that it is a localized art form that springs forth from a specific community to define a specific time and place and the lyricist, a poetic scribe, shares…

-

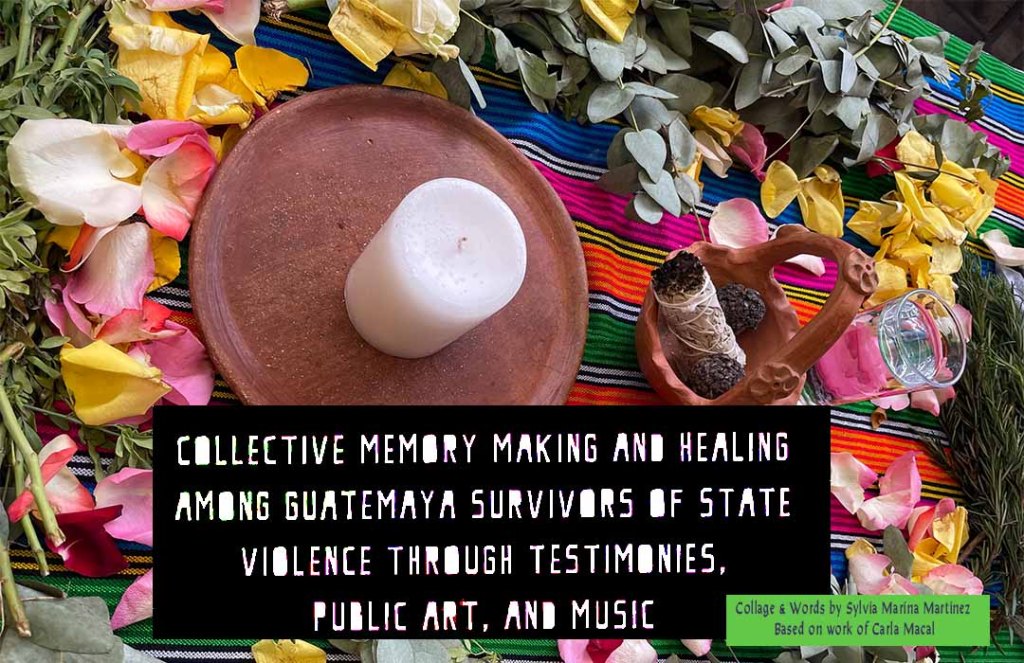

Collective memory making and healing among GuateMayan survivors of state inflicted violence through embodied testimonies, public art, and music.

Two weeks ago, I published a blog post on the mural & graffiti art and hip-hop music of Lakota artists Derek Smith and Talon Bazille, respectively. As I was writing that post I was simultaneously working on a collage art piece for my cousin’s dissertation to illustrate the concept of cuerpo territorio amongst Indigenous GuateMayan…

-

Multi-instrumentalist and Grammy-winning songwriter Dom Flemons illuminates hidden American history in his music.

in Bluegrass, Blues, Chicago, Country, Cowboys, Folk, Guitarists, Harmonica, Nashville, Piedmont bluesDom Flemons, the Grammy-winning multi-instrumentalist, singer, and songwriter is a veritable musicologist of American folk music. I first heard Dom in his work with the Carolina Chocolate Drops back in my days working as the American Roots genre manager at the Grammys. Many of his solo albums since the days of that band have been…

-

The blues according to Nina Simone: my ode to Queen Nina

What hasn’t been said or written about Queen Nina Simone? She has been called an icon, a legend, and a genius, and she is one of my favorite artists of all time and I would be remiss if I didn’t use my blogging platform to honor her music – especially her love of blues and…

-

Anaïs Mitchell’s folk opera: Hadestown

I’ve wanted to share about this album for a couple of years. The album, Hadestown, is the creation of folk singer-songwriter Anaïs Mitchell (who has released a more recent album this year, Young Man in America, which is awesome too). Hadestown was released in 2010 on Righteous Babe Records (Ani DiFranco‘s label), and I loved…