Tag: Bazille

-

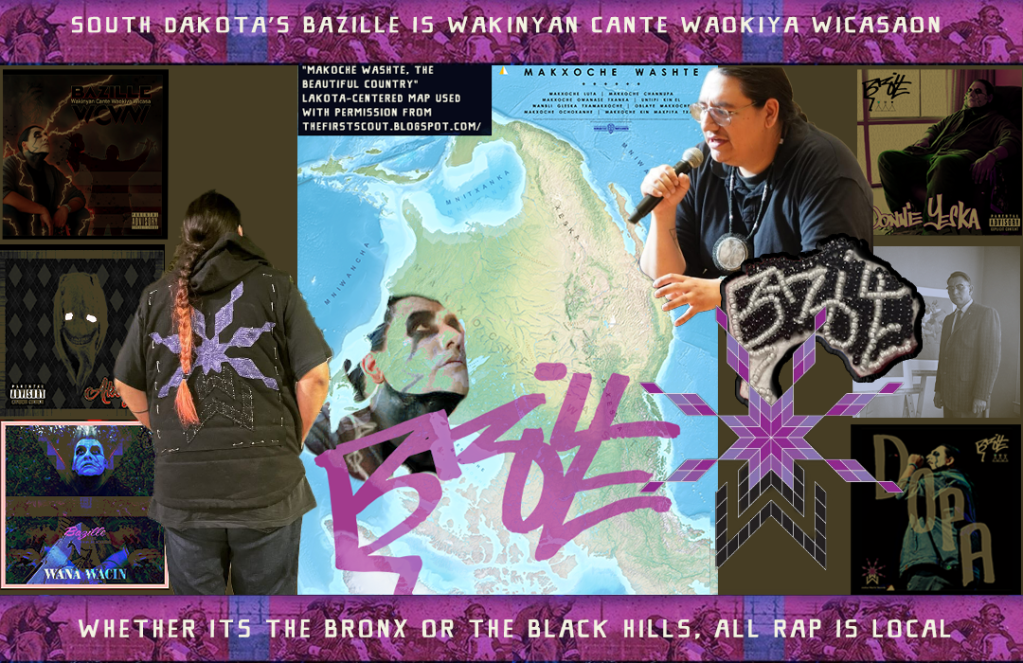

South Dakota’s Bazille is Wakinyan Cante Waokiya Wicasaon

Whether its the Bronx or the Black Hills, All Rap is Local I’ve always thought of rap as a form of folk music or street journalism such that it is a localized art form that springs forth from a specific community to define a specific time and place and the lyricist, a poetic scribe, shares…

-

Reclaiming Lakota narratives & sovereignty: Hip-hop, graffiti art, creating lyrical medicine

Lakota graffiti artist, muralist and community organizer Derek “Focus” Smith has been challenging the power structure of the “Mississippi of the North” since the early 2000s bringing the power of graffiti and muralism to the Reservation and using his craft to tell the stories of Lakota history and encourage the youth. The art has taken…