Category: Hip Hop

-

Let’s take a ride down memory blvd: Kendrick Lamar’s Squabble Up

Art by Author The excitement I felt when I heard the Debbie Deb sample on Kendrick Lamar’s Squabble Up off his new GNX project was overwhelming. It took me right back to being 12 and starting to navigate the treacherous teenage years with the help of music. The first record I remember buying was Fascinated…

-

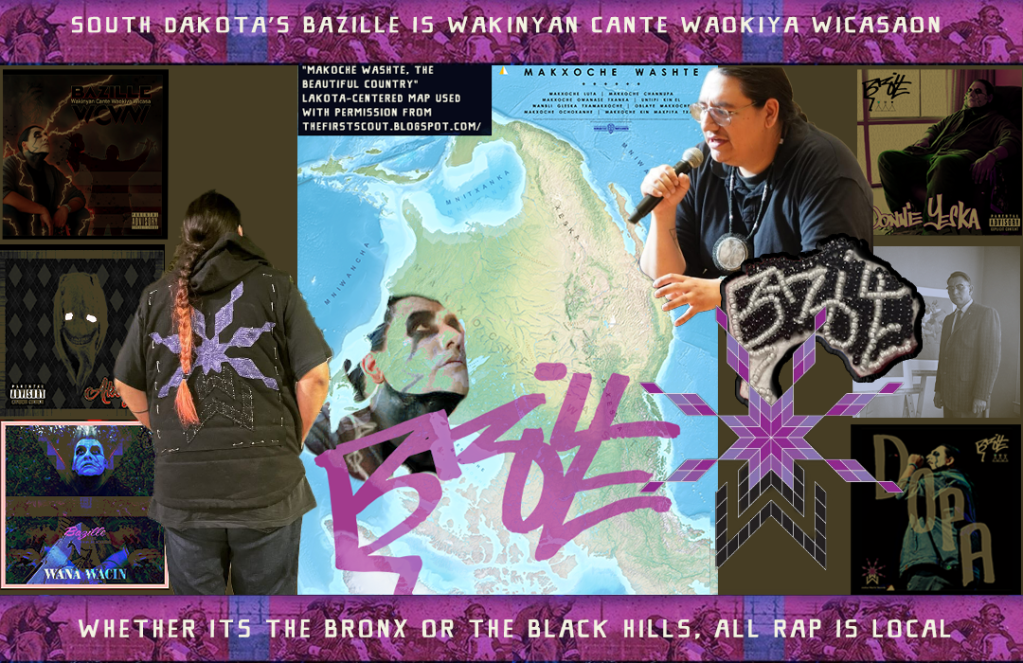

South Dakota’s Bazille is Wakinyan Cante Waokiya Wicasaon

Whether its the Bronx or the Black Hills, All Rap is Local I’ve always thought of rap as a form of folk music or street journalism such that it is a localized art form that springs forth from a specific community to define a specific time and place and the lyricist, a poetic scribe, shares…

-

Staying true to his Philly roots, Chase Flow’s Hip-Hop odyssey takes him around the world

I first met Chase “Flow” Bradley at least 10 years ago when I was working at the Grammy Awards. I can’t remember the context but I do remember him being a genuine and consistently cool person as well as a multi-talented, multi-disciplinary rapper, DJ, and producer dedicated to not only his craft but also to…

-

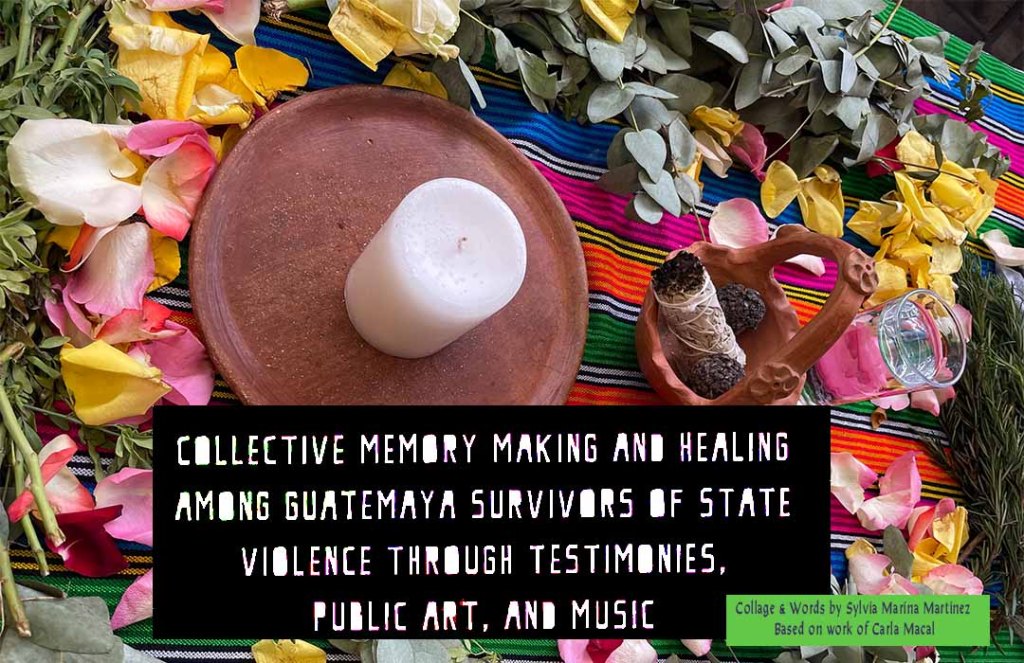

Collective memory making and healing among GuateMayan survivors of state inflicted violence through embodied testimonies, public art, and music.

Two weeks ago, I published a blog post on the mural & graffiti art and hip-hop music of Lakota artists Derek Smith and Talon Bazille, respectively. As I was writing that post I was simultaneously working on a collage art piece for my cousin’s dissertation to illustrate the concept of cuerpo territorio amongst Indigenous GuateMayan…

-

Reclaiming Lakota narratives & sovereignty: Hip-hop, graffiti art, creating lyrical medicine

Lakota graffiti artist, muralist and community organizer Derek “Focus” Smith has been challenging the power structure of the “Mississippi of the North” since the early 2000s bringing the power of graffiti and muralism to the Reservation and using his craft to tell the stories of Lakota history and encourage the youth. The art has taken…

-

Words and sounds that inspire at the start of 2014: from the city of angels with love

“The hope of a secure and livable world lies with disciplined nonconformists who are dedicated to justice, peace and brotherhood.” ~ MLK, Jr. The year 2014 is upon us and as we come to terms with tragic consequences of global apathy, the creative mind and spirit of the earth and universe instills in us the…